Many custom options...

And formats...

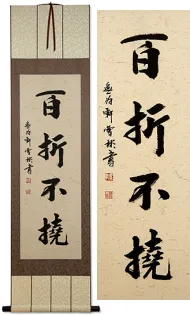

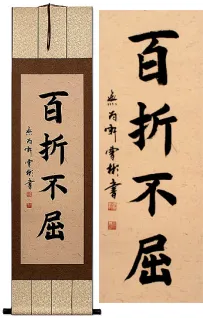

Undaunted After Repeated Setbacks in Chinese / Japanese...

Buy an Undaunted After Repeated Setbacks calligraphy wall scroll here!

Undaunted After Repeated Setbacks

Persistence to overcome all challenges

百折不撓 is a Chinese proverb that means “Be undaunted in the face of repeated setbacks.”

More directly translated, it reads, “[Overcome] a hundred setbacks, without flinching.” 百折不撓 is of Chinese origin but is commonly used in Japanese and somewhat in Korean (same characters, different pronunciation).

This proverb comes from a long, and occasionally tragic story of a man that lived sometime around 25-220 AD. His name was Qiao Xuan, and he never stooped to flattery but remained an upright person at all times. He fought to expose the corruption of higher-level government officials at great risk to himself.

Then when he was at a higher level in the Imperial Court, bandits were regularly capturing hostages and demanding ransoms. But when his own son was captured, he was so focused on his duty to the Emperor and the common good that he sent a platoon of soldiers to raid the bandits' hideout, and stop them once and for all even at the risk of his own son's life. While all of the bandits were arrested in the raid, they killed Qiao Xuan's son at first sight of the raiding soldiers.

Near the end of his career, a new Emperor came to power, and Qiao Xuan reported to him that one of his ministers was bullying the people and extorting money from them. The new Emperor refused to listen to Qiao Xuan and even promoted the corrupt Minister. Qiao Xuan was so disgusted that in protest, he resigned from his post as minister (something almost never done) and left for his home village.

His tombstone reads “Bai Zhe Bu Nao” which is now a proverb used in Chinese culture to describe a person of strong will who puts up stubborn resistance against great odds.

My Chinese-English dictionary defines these 4 characters as “keep on fighting despite all setbacks,” “be undaunted by repeated setbacks,” and “be indomitable.”

Our translator says it can mean “never give up” in modern Chinese.

Although the first two characters are translated correctly as “repeated setbacks,” the literal meaning is “100 setbacks” or “a rope that breaks 100 times.” The last two characters can mean “do not yield” or “do not give up.”

Most Chinese, Japanese, and Korean people will not take this absolutely literal meaning but will instead understand it as the title suggests above. If you want a single big word definition, it would be indefatigability, indomitableness, persistence, or unyielding.

See Also: Tenacity | Fortitude | Strength | Perseverance | Persistence

This in-stock artwork might be what you are looking for, and ships right away...

Gallery Price: $150.00

Your Price: $99.88

Gallery Price: $180.00

Your Price: $99.88

Gallery Price: $108.00

Your Price: $59.88

Gallery Price: $162.00

Your Price: $89.88

Gallery Price: $200.00

Your Price: $98.88

The following table may be helpful for those studying Chinese or Japanese...

| Title | Characters | Romaji (Romanized Japanese) | Various forms of Romanized Chinese | |

| Undaunted After Repeated Setbacks | 百折不撓 百折不挠 | hyaku setsu su tou hyakusetsusutou hyaku setsu su to | bǎi zhé bù náo bai3 zhe2 bu4 nao2 bai zhe bu nao baizhebunao | pai che pu nao paichepunao |

| In some entries above you will see that characters have different versions above and below a line. In these cases, the characters above the line are Traditional Chinese, while the ones below are Simplified Chinese. | ||||

Successful Chinese Character and Japanese Kanji calligraphy searches within the last few hours...